By Charlie Wyatt

It was mid-summer 1963 and I was a newly commissioned officer in the Navy. My ship, the USS Saint Paul, was headed for Hawaii for a short three day visit.

We pulled into Pearl Harbor Wednesday evening just at sunset. I had the duty that night and into Friday, so I couldn’t leave the ship. My roommate, Dave Pearson, was off with first gangplank over, equipped with some of my cash and orders to bring back an aloha shirt for me. On liberty in Hawaii, the approved dress code was either full uniform, a coat and tie or aloha shirt and slacks. He returned with the loudest blue one imaginable and a receipt for the, at that time, incredible sum of thirty-eight dollars. He patiently explained it was a genuine Duke Kamahama, carved wooden buttons and everything. Accordingly, when liberty call sounded at 4:00 PM, we hit the beach, or more exactly the long wharf where we tied up. A couple of other junior officers, Todd Barthold and Bob Stuart went with us.

Todd had rented a Chevy convertible for the weekend for only twenty-nine ninety-five, which we all split, as that came to about the same as several taxi rides and besides it was cool. We didn’t even use the car for our first stop, which was the air conditioned Officer’s Club across the wharf and down a ways.

I was informed that the most junior officer, which was me, always bought the first round

. Four mai-tai’s come to about ten dollars but as we downed those, the others confided that I was home free for the rest of the evening. After another round, paid for by Dave, we decided to adjourn to Fort Derussey, a couple of miles down the beach, where the mat-tai’s were reputed to be bigger and better. Actually, they were only a tad bigger. I couldn’t tell any difference in quality, although as pretty much of a beer drinker, I wasn’t any kind of expert. After two rounds there and debating whether to have dinner, somebody had the bright idea to cruise downtown Honolulu, which we did. It was getting into the main part of the night when, it was decided, I don’t know by who, that we needed to take in Don Ho’s show at his place on the main drag.

To my surprise, rather than tables scattered around, the seating was almost theater like, in rows. Once settled in, an attractive young lady wearing a sarong, I think it’s called, took our drink orders. Or rather Todd’s, who tended to get louder as the night wore on and the drinks mounted up.

“Mai-tails for me and my friends, sweetheart, and a kiss from your sweet lips, I beseech you.”

She whisked away and returned with four monster sized drinks. Todd, who was feeling generous, and had wealthy parents, waved away our half-hearted attempts to contribute and plopped a twenty on her tray. Observing her still standing there, he said,

“No, it’s all yours, sweetheart, keep the change.”

She said, “Thanks, but that’ll be a two dollars more”, a distinct pause, “sweetheart.”

Red faced he added a five to the tray. She left, without giving him the desired kiss, but he did get some chuckles from us and nearby patrons. After a long delay, Don Ho did take the stage and we were subjected to several hours of what sounded to me like endless variations on ‘Tiny Bubbles in the Wine’. Toward the end of the evening an marine major in uniform came in and sat near us. Todd engaged him in conversation, as the music permitted. He insisted on buying us a round. When the evening ended, we all trooped outside and the major shook everybody’s hands and said he was off to find a cab for the long ride home, somewhere up past North Beach. Todd said,

“Nonsense, we’ve got a car right here, we can run you there, no sweat.”

He protested, but in the end I rode in the front with Todd driving and the others in the back seat. It was a warm night, overcast with only a sliver of a setting moon, so it was pleasant to tool along the smooth road, frequent glimpses of surf on our right as we went.

I was a little concerned about Todd driving after all the drinks, but he seemed to be okay. Late as it was, there was virtually no traffic. We finally got to the complex of houses and cottages where the major lived. He directed Todd through a few branching streets and turns until we delivered him at his place. We wound our way back to the highway just after 2AM and headed for the base. After about thirty or forty minutes, I said,

“We should be coming up to the edge of Honolulu by now, but it’s just getting darker and there’s nothing around here but pineapple fields, what’s wrong?”

“Nothing’s wrong. You probably didn’t remember how long it took to get there, so it’s gonna’ take just as long to get back.”

After another ten minutes I said,

“Stop the car.”

He looked at me, but eased over on the shoulder and stopped.

I said, “Look out there. What do you see?”

Humoring me, he said, “Appears to be the Pacific Ocean, unless I’m badly mistaken”

“Correct, and it’s on our right hand side, same as it was when we were taking the guy home. If we were headed back, it ought to be on our left. You turned the wrong way coming out of the complex.”

The two in the back seat, who had been asleep, now joined in the argument. I dug out the roadmap the car rental company puts in the glove compartment.

“Look, here’s that Waimai Village where the major lives. We’ve gone way past that. I think were just about at the top of Oahu.”

After some argument, it was decided it would be just as quick to continue around the island as it would be to turn around and have to go through downtown Honolulu to Pearl. Dave and Bob went back to sleep, but I determined to stay awake and make sure Todd did. Conversation petered out, so I tried the radio. Unfortunately the only all night station I could bring in played nothing but Hawaiian music, every other song, it seemed, by Don Ho

. It was well after dawn when we got back to the base and six-forty-five when I stumbled up the gangplank. The full horror of my situation hit me as I saw a work detail laying out our ceremonial red carpet on the quarterdeck. It was Saturday, normally a day of holiday routine, which meant I could sleep in as long as I wanted. This Saturday, though, our ship, the flagship of the Admiral of First Fleet, was hosting a morning brunch for every high muckety-muck in Hawaii, military & civilian. Worse, I was the Officer of the Deck, meaning I was on duty, there on the quarterdeck from 7:30 to noon. With no time for sleep or even breakfast, I went below for a rushed shower and to struggle into full dress white uniform. This has to be the most uncomfortable uniform ever devised, especially in the tropics. The coat is some sort of heavy starched material, which fastens with hook and eye just under the chin.

I made up to the quarterdeck with a minute to spare and took over the watch. The executive officer, a fuss budget of the first order, was on the scene not two minutes after that.

“Everything squared away and ship shape, Mr. Wyatt? I needn’t tell you how important that this goes without a hitch.”

In one of the most blatant lies in a lifetime of stretching the truth, I answered,

“Yes, sir. I’ve got everything under control”

When he left, after personally straightening out two minute wrinkles in the red carpet, I turned to the chief boatswain’s mate who was a veteran of these affairs and said,

“Chief, please don’t let anything happen. If this thing gets screwed up, it’s our necks in a noose.”

He looked at me straight faced and said.

“No, sir, with respect, it’s your neck. Green Ensigns are expendable, senior chiefs are valuable and protected.” Then he grinned and said. “Don’t worry. All we have to is announce the brass as they come on and have the side boys in place. Piece of cake.”

Side boys are one of the Navy’s archaic customs, sailors in full dress who stand either side of the head of the gangplank and salute as the visitor is piped aboard.

Captains and minor officials rate four side boys full admirals and some civilians rate eight. In this case the captains of other ships started arriving at 9:00. As each one would pull up at the head of the wharf, we had a guy there with a walky-talky who would ask who the dignitary was, rely it to a sailor standing by the quarterdeck who would then announce it over the ship’s loudspeakers. For example the captain of the USS Helena would be “Helena, arriving” command officers are abbreviated; CINC PAC FLT would be Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet.”

By 9:30 I was suffering the agonies of the damned, sweating from every pore, pounding headache and a vague queasy feeling. The badge of office for the officer of the deck in port is a large, heavy brass telescope, another archaic Navy custom. What with toting that tucked in my let arm and standing at stiff attention and holding a salute with my right arm every minute or so, I was getting fatigued and the most important visitors were yet to come. The chief was aware of my distress and in a brief quiet moment, beckoned me into the pilot house just behind the quarterdeck.

“Here, drink this.”

It was a tall glass of ice water with a pitcher of more sitting nearby. There was a large pan of ice and water, with towels beside it. I drank the glass in three gulps, dipped a towel in the ice water and mopped my face and dried off with another.

“God bless you, Chief, and your children and their children unto the fifth generation.”

I somehow got through the higher-ups right up to CINC PAC, the admiral in command of all military in the Pacific. I ducked back in the pilot house and said,

“Don’t call me out there for anybody but President Kennedy”

A few minutes later he poked his head in and said

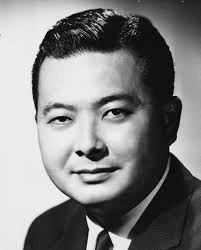

“It ain’t the president, but the next thing to it, Inouye.”

I suppose I wasn’t at my best, because I replied ,

“Whatta you mean in a way? What way? What do you mean?”

“Not in a way, Inouye”

“What the hell does in no way mean?”

“Inouye, Senator Daniel Inouye”

By then the black limo was pulling up at the foot of the gang plank. I panicked.

“How many side boys? How do we announce him?’

The chief remained calm. “Eight side boys on the double. Announce him as Senator Inouye.”

I knew who he was, a Medal of Honor winner in WW II, who had lost his right arm in that action. I had the brief weird thought,

“How is he gonna return the salute with no right arm?”

then felt dumb as he strode briskly by and snapped off a return salute with his left.

For the next hour I divided my time between gazing across the harbor at the Arizona Memorial and envying the men there who were already dead and beyond hangovers and mentally cursing the few individuals I could see entering the air conditioned officer’s club. The visitors left, in reverse order of their arrival, this time with the captain and X.O. on deck to wave them goodbye. Finally noon came and my relief a snotty ensign all of four months my senior arrived. He was wearing casual tropical whites, a short sleeved white shirt with open neck, no tie.

He looked me up and down.

“Look a little seedy, Wyatt. Make an effort to sharpen up, would you.”

I refrained from hitting him with the telescope, merely surrendering it with the heartfelt comment, “It’s all yours, baby.”

I went below and realized I hadn’t had anything of substance to eat since noon the day before. I didn’t feel like a formal meal, but I convinced a steward to let me have a peanut butter sandwich and some chocolate milk.

I went to my room, stripped off that torture suit and fell into my rack. Two hours later a was blasted awake by the ship’s loudspeaker. “Now this is a drill, this is a drill, General quarters, all hands man your battle station.”

Curses! I had forgotten that the ship was scheduled for gunnery practice that afternoon. I scrambled into some pants and ran up to my battle station, the five inch gun on the port side. Naturally I didn’t have my earplugs with me, and the crew had none to spare. For the next two hours, my ears were blasted with the sound of shells being fired approximately eight feet away. In between the five inch firing, the eight inch triple turrets went off, shaking the whole ship and giving me yet another headache. When we secured from general quarters, I went back to bed and slept fourteen hours straight. As we were leaving Pearl Monday morning, I was in my usual station, on the signal bridge with my division. My first class signalman was beside me watching Diamond Head slowly sink into the ocean as we headed East. He gave a small but audible sigh,

“I always like going there and hate to leave. This was your first time here, wasn’t it sir? Whatta’ ya think?”

I didn’t look around. “I hope the whole Godforsaken island slides under the ocean.”

He drifted away, but I heard him caution the other men,

“Stay away from Mr. Wyatt, he’s in a foul mood about something’”

Many years later, not long after I was married, without my knowledge, my bride threw away my aloha shirt, on the grounds that it was so gaudy that she wouldn’t be caught dead with anybody wearing it.

When I found out, I didn’t tell her it was then worth four or five hundred dollars. Probably just as well. Not the sort of visit I would want to have a souvenir of anyway.