By Mike Allen

February 16, 2023 (Santee) — Customers of the Padre Dam Municipal Water District are getting some relief on their usually hefty bills, thanks to a vote last year by its board to freeze rate increases over five years.

February 16, 2023 (Santee) — Customers of the Padre Dam Municipal Water District are getting some relief on their usually hefty bills, thanks to a vote last year by its board to freeze rate increases over five years.

But that freeze only applies to internal rate increases, not those imposed by outside agencies such as the San Diego County Water Authority (CWA) and San Diego Gas & Electric (SDGE), both of which are charging more for their services.

Aware that those entities were imposing price hikes, Padre Dam’s five-member board decided in June to use funds it received from a big legal settlement from a prolonged legal battle between the CWA and the Metropolitan Water Authority, headquartered in Los Angeles.

The settlement share accorded to Padre Dam (one of 24 water districts in the county) was nearly $2.3 million, and offset higher water rates by CWA starting last year, and continuing through 2024.

To soften the sting from CWA’s increases (which were caused by the Metropolitan Authority imposing higher rates), the district allotted about $608,000 last year, some $712,000 this year, and the remaining $968,000 for the following year.

Those allocations still won’t protect customers from higher bills starting in July when this year’s legal settlement subsidy expires, said Padre Dam CEO and General Manager Kyle Swanson (photo, right).

Due to CWA’s higher rates, the typical Padre Dam customer will see their water bill jump by $4.17 or 3 percent monthly. That means the typical residential customer’s bill will rise from $127.96 to $132.13, he said.

Because of increased hikes by SDG&E, those Padre Dam customers paying for pumping costs will see their bills rise by another $2.31, the district said. Swanson said about 40 percent of Padre Dam’s customers are affected by the higher electricity costs.

In a press statement about the rate freeze, Padre Dam said the board made the decision to provide some relief in the face of unprecedented higher inflation, and because of “the District’s strong financial position of the water and wastewater operating funds.”

According to the district’s annual report for the 2022 fiscal year that ended June 30, all four Padre Dam divisions—potable water, sewer, recycled water, and Santee Lakes park—showed net profits. The net change in assets for water was $14 million; for sewer, $4.5 million; for recycled water, $2.5 million, and for parks, $1.38 million.

Swanson asserted that the district, just as all government agencies, do not make any profits. He said all excess cash— after operating expenses, debt and capital replacement costs are subtracted— goes back into the reserve balance “to be used for both planned and unplanned expenditures.”

“Padre Dam does not make a profit,” Swanson said.

Among the biggest planned expenses Padre Dam has in partnership with four other agencies is the Advanced Water Purification Program (AWP), which began construction last May. The project will take some 15 million gallons of sewage now pumped to San Diego’s Point Loma treatment plant to a massive new treatment and purification plant just north of Santee Lakes to produce some 11.5 million gallons of potable water.

Photo, right: Mission Gorge pumping station, courtesy of Padre Dam Municipal Water District

From an initial estimate of $475 million, the project cost is now targeted to come in at $950 million that is shared by the city of El Cajon, San Diego County, and Helix Water District and Padre Dam. The four agencies formed a joint powers authority to create and manage the AWP.

AWP’s goal is to reduce the dependence on importing water while creating a more dependable source that will provide up to 30 percent of the region’s supply, and reduce the amount of wastewater discharge into the Pacific Ocean.

Padre officials say AWP should stabilize customer bills because the district would have a local supply of water at lower cost than buying it from CWA. The Santee-based Padre Dam covers 73 square miles and serves parts of El Cajon, Lakeside, Flinn Springs, Harbison Canyon, Blossom Valley, Alpine, Dehesa and Crest. It has about 104,000 residents.

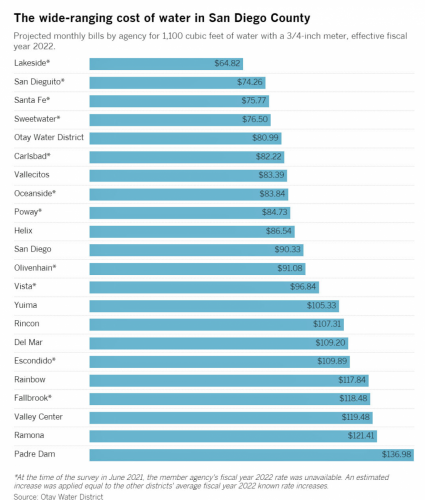

Padre’s size and the fact that water must be pumped to higher elevations are the main reasons for the district’s historically exorbitant rates. According to a rate study done by the Otay Water District, Padre Dam’s water rate for last year was the highest among the 24 water districts in the county at $136.98 per month.

The next highest was Ramona at $121.41. Lakeside was the lowest with a monthly bill of about $65.

Brett Sanders, Lakeside’s general manager, said his district benefits from having a local source of groundwater that provides about 20 percent of the supply. “Our overhead is low (14 direct employees) and we try to outsource a lot of different functions such as engineering and architectural.”

Lakeside also services about 7,000 connections (versus about 39,000 connections for Padre Dam), and some 35,500 in population.

Mark Robak, president of the board of Otay Water District in Spring Valley, says that there are too many water districts in San Diego County. Each of these government agencies employ highly paid executives and staffers, and routinely hire high-paid consultants to manage expensive pipelines and other infrastructure necessary to deliver water to customers.

Robak said he talked about various consolidations of districts when he served on the Padre Dam board from 1996 to 2000. One potential merger between Fallbrook Water District and Rainbow Water District didn’t happen because some board members didn’t want to lose their positions, he said.

“There’s a reason (consolidations) don’t happen,” he said. “It’s not because the highly paid employees don’t want it. It’s because of the directors. They don’t want to lose their seats.”

One small merger that occurred in 2006 between Lakeside and Riverview Water Districts resulted in cost savings that helped customers in the merged district to enjoy the lowest rates in the county, Sanders said.

“It’s absolutely benefited us,” he said. “Before we had two GMs (general managers) and now we have one. The administrative staff and operating staff were streamlined.”

At Helix Water District based in La Mesa with a service area of about 50 square miles and a population of 277,000, the average monthly bill this year is $89.45, but that doesn’t include sewer, said Helix spokesman Mike Uhrhammer. Although Helix has access to local water supply at Lake Cuyamaca, in most years that supply is negligible. This year due to all the rain in the mountains, Helix expects to use about 2,900 acre feet for its water supply, he said.

An acre foot is the amount of water to cover one acre by one foot deep, and is about 326,000 gallons.

While the cost savings from consolidation would seem evident, practically all the water officials said they were opposed to such combinations.

“We just don’t hear much talk about that, said Uhrhammer. “Water has always been super local.”

“I like to see local control of government agencies,” Sanders said. “Special districts have a positive influence on the community and can be efficient.”

Swanson of Padre Dam said his district “offers a high level of service to our customers….I think people enjoy the ability to come in person into our lobby. They’re able to (personally) reach out to our board members….When you get larger sometimes you lose some of those conveniences.”

Asked if the subject of consolidation has ever been raised in recent years as a way to save money and keep rates at a reasonable level, Padre President Bill Pommering (photo , left) said, “Not to my knowledge.”

Swanson said for the subject to be considered by Padre, “it would have to come from interest in the community.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly identified which two water districts rejected a potential merger. The districts that opted against a merger were the Rainbow and Fallbrook districts, according to Robak.